Garima Kaushiki | 7th September 2025

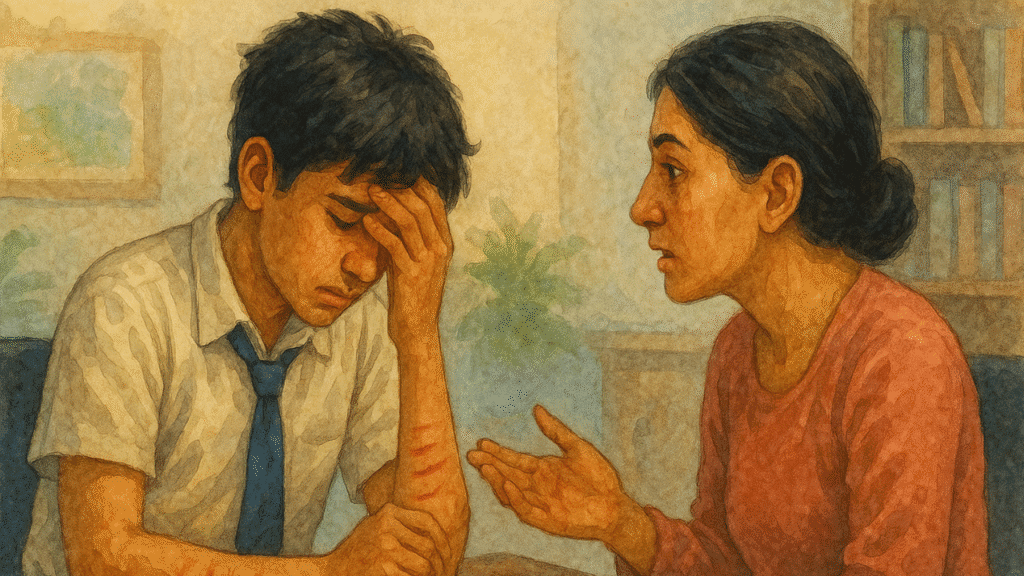

Radha was 13 when her parents first noticed she was eating less and spending more time in her room. She was once the girl who raced friends on the playground, but now she barely stepped outside. Instead, she scrolled endlessly on her phone, glued to Instagram and short videos.

At first, her parents assumed it was just “teenage mood swings.” Her teachers thought she had become “lazy” and “unfocused.” But the signs grew sharper. She posted cryptic late-night messages. She began comparing herself to “perfect” peers online — their vacation photos, toned bodies, and flashy gadgets. Gradually, Radha’s laughter faded into silence.

No one knew she was battling deep feelings of inadequacy. And no one in school was trained to ask the right questions. Her distress was invisible, until it wasn’t.

Childhood in the Age of the Scroll

Radha’s story is not unique. Across India, millions of children are growing up with phones in their hands before they even step into adolescence. Social media exposes them to worlds they are too young to process — curated perfection, cyberbullying, unrealistic standards of beauty, and often explicit content.

For many children, like Radha, there constant exposure quietly shapes how they see themselves. They internalise shame, fear, or inadequacy. But unlike adults, they lack the vocabulary to say, “I feel anxious,” or “I feel depressed.” Instead, they show it through behaviour — withdrawal, irritability, sleep changes, loss of appetite.

Without trained counsellors in schools, these red flags are brushed off as “attitude problems” or “teenage rebellion.” And by the time the problem is recognised, it often requires far more serious intervention.

The Invisible Mental health Crisis

The National Mental Health Survey estimates that at any given time, 2.2 crore Indian children need psychological support. Add to there the explosion of social media use among teenagers, and the problem grows sharper.

A 2022 UNICEF study found that over one-third of Indian adolescents felt anxiety or sadness linked to social media comparison. Cyberbullying is on the rise, with NCRB reporting thousands of cases annually, though most go unreported.

And yet, in the very space where children spend the bulk of their day — schools — professional mental health support remains absent. The Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) requires all schools to appoint counsellors. But surveys reveal only around 3% comply.

So what happens to the other 97% of children like Radha? They struggle alone, their pain misread, their silence untreated.

Teachers Cannot Do It All

Schools often argue that teachers can guide students through such challenges. But there is a dangerous myth.

- Teachers are trained to teach. Their focus is on academics, lesson planning, and classroom management.

- Counsellors are trained to listen. They study child psychology, developmental behaviour, and crisis intervention.

Expecting teachers to double up as counsellors is like expecting a math teacher to also be the school doctor. Good intentions are not enough when children’s mental health is on the line.

Radha’s teachers scolded him for being “lazy.” A counsellor would have asked why. That difference can determine whether a child finds help or sinks further.

The Academic Argument

For school leaders hesitant about the “cost” of counsellors, there is a more practical argument: counselling directly improves academic outcomes.

- Trauma and anxiety disrupt memory, focus, and learning.

- Students struggling emotionally are more likely to skip classes, perform poorly, or drop out.

- Schools that employ counsellors report fewer disciplinary issues and higher exam results.

In Radha’s case, her declining focus was not a lack of ability but an overflow of unaddressed anxiety. If her school had provided a safe space with a counsellor, her emotional stability could have supported her academics — instead of undermining them.

So the real question is not whether schools can afford counsellors. It is whether they can afford the cost of neglecting them.

Global Standards, Local Neglect

Across the world, counselling is considered a non-negotiable part of education.

- In the United States, school counsellor-to-student ratios are often regulated at 1:250.

- In Finland, school psychologists are treated as essential staff.

- In Singapore, counselling is integrated into the national education framework.

India, however, continues to treat counsellors as a luxury for elite private schools. Government and low-fee private schools — where children may be most vulnerable — often have no such resource. Which leaves us with an uncomfortable question: Are we willing to accept a system where access to emotional safety depends on privilege?

What Must Change

Experts outline clear steps to address this gap:

- Mandatory compliance audits by CBSE and state boards.

- Public funding support so government schools can afford counsellors.

- Shared counsellor networks for clusters of smaller schools.

- Teacher sensitisation programs to identify early red flags.

- Parent advocacy — treating counsellors as non-negotiable, like buses or labs.

- Destigmatising mental health — campaigns to normalise counselling as routine.

But while the solutions exist, the harder question remains: what will make schools act?

The questions we must ask

Radha’s story is not just about one girl. It is about an entire generation navigating adolescence in an online world, without the emotional anchors previous generations had. Schools are supposed to be those anchors. Yet most function without trained counsellors, leaving children to cope alone.

So we are left with open questions:

- How many Radha’s will it take before schools recognise counselling as essential, not optional?

- Should parents accept schools without counsellors in the same way they wouldn’t accept schools without safe drinking water?

- And who will push harder for change — policymakers, principals, or parents themselves?

There are no easy answers. But one truth remains: childhood is too fragile, too precious, to leave unsupported in the age of the scroll.

Garima Kaushiki is a media researcher and writer with a focus on education, child rights, and mental health. She combines data-driven insights with human stories to highlight systemic gaps and advocate for meaningful change.