Aishwarya Rajput | 25th November 2025

Bollywood has always been a mirror of Indian society, being contemporary to its time, reflecting its dreams, anxieties, prejudices, and aspirations. It matched the trend of its time, making cinema more relatable to its audiences. But, when it comes to portraying LGBTQ+ identities and non-traditional family dynamics, mainstream cinema has always treaded with caution. In this scenario, director Anand Tiwari’s Maja Maa emerges as a soft-spoken yet significant narrative, one that gently nudges Indian audiences toward a more inclusive understanding of identity. It brings queer representation directly into the heart of the Indian middle-class family, advocating for empathy through everyday storytelling.

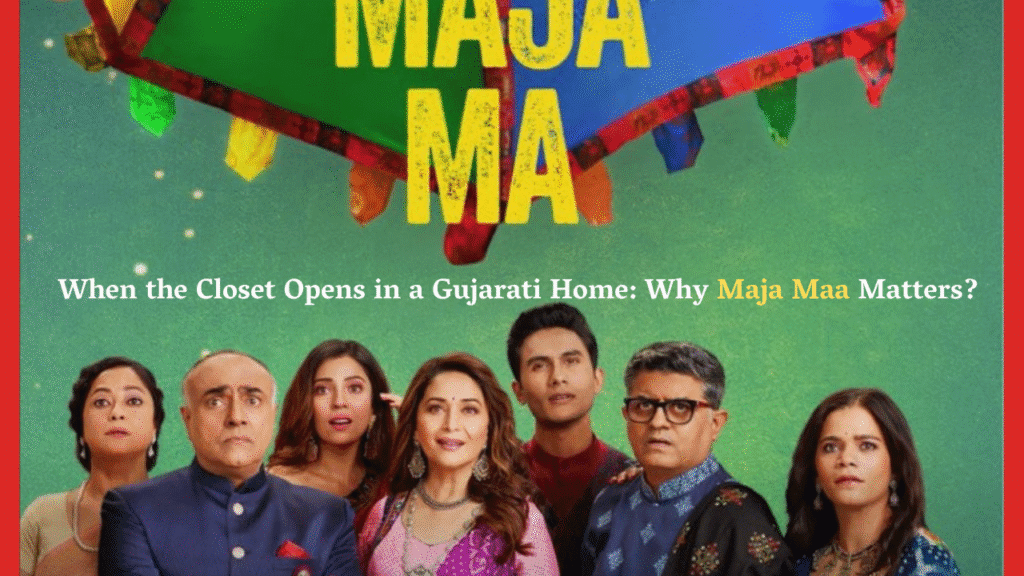

At its core, Maja Maa is the story of Pallavi Patel (Madhuri Dixit), a seemingly “perfect” homemaker whose quiet revelation about her sexuality becomes a trigger for examining societal expectations, family relationships, and unconditional love. In a country where discussions around queerness still collide with cultural conservatism, Maja Maa brings queerness not on society’s margins, but within the domestic centre.

Challenging norms through familiarity

Maja Maa is a unique film that chooses familiarity over shock value to reveal Pallavi’s identity. Pallavi is not portrayed as someone who is struggling with her identity or trying to fit; instead, she is already established, with a loving family of two kids, and everyone in her area respects her. She is famous for her dancing and cooking. She runs her own dance class and lives a normal, ordinary life. This narrative choice subtly conveys an advocacy message: LGBTQ+ identities are not deviations from family life; they are part of its fabric.

There have been several films in Bollywood on LGBTQA+ representation. But what makes this film a big, risky and unique step was to present a middle-aged woman, a mother of 2 kids, at the centre of the narrative, as a lesbian. This film challenges patriarchal limits around womanhood. Pallavi’s journey underlines that women’s identities are not static; they evolve across age, experience, and emotional awakening. This reframing is culturally significant, as Indian cinema often sidelines older women or restricts them to supporting roles without having their own sense of personal autonomy. Maja Maa advocates for the recognition of women’s interior lives, sexual, emotional, and personal, well-being beyond their roles as wives and mothers.

Normalising Queer identity through Cultural proximity

The greatest strength of the film lies in its normalisation of queer identity within the Indian family structure. The film situates it in a vibrant Gujarati household, a setting that demonstrates tradition, festivity, and community honour. This contrast of community and society’s expectation of a woman, especially a mother, and her own identity is deliberate and impactful.

The film invites viewers to imagine queerness not as a rupture from tradition but as a reality coexisting within it. For many Indian households unaccustomed to discussing sexuality openly, seeing these themes unfold through an everyday family lens encourages conversations that otherwise remain suppressed. The media consistently shows, representation that feels “close to home” has a stronger potential to shift attitudes than narratives that appear distant or niche.

Emotion as a tool

Maja Maa builds empathy through relatable characters and emotional conflict. Pallavi’s son grapples with feelings of betrayal, not because he rejects his mother’s identity, but because he mourns the loss of an image he had held of her. Her husband struggles with internalised beliefs but is torn by love. Even societal reactions, though harsh at times, emerge from familiar patterns of cultural conditioning rather than villainy. Pallavi herself was not able to accept her identity, and that was the main reason she didn’t elope with Kanchan. She thought that there was something wrong with her, and she could not try to choose her happiness, neither when she was young nor after her marriage, because that would destroy her family.

This emotional realism allows audiences to see themselves in the characters. The film suggests that acceptance is not a switch one flips instantly; it is a journey shaped by vulnerability, discomfort, and ultimately, love. The journey of acceptance by Pallavi’s family is shown in a raw and natural way. The family went through an emotional turmoil after the image of a perfect wife, mother and woman was shattered. The stretch and tension were perfectly captured in their internal relationship. The film invites viewers into a shared human experience rather than confronting them with ideological rigidity.

Representation with a purpose

The film represents progress because it chooses to highlight a demographic often erased in conversations about sexuality: middle-aged queer women. Indian cinema rarely offers space to explore identities among older women, whose inner lives are routinely overshadowed by younger characters or heteronormative romance. By giving Pallavi the platform to articulate her truth, the film implicitly advocates for a broader understanding of queer representation, one that includes diversity in age, gender, and experience.

The film also pushes back against the stereotype that queer narratives must revolve around trauma. While Pallavi faces challenges, her story is not defined by violence or tragedy. Instead, Maja Maa builds a narrative where dignity, self-respect, and self-discovery guide the arc of the protagonist. This approach broadens the possibilities for inclusive storytelling: that some can centre on healing.

A step toward future inclusivity

While Maja Maa may not be a perfect film, its contribution to India’s evolving cultural landscape is undeniable. Movies like Shubh Mangal Zayada Saavadhan, Badhai Do, Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui, and Ek ladki ko dekha toh aesa laga open doors for more nuanced representations, proving to Bollywood that audiences are ready, even eager, for diverse, inclusive narratives. For media creators, it serves as a reminder that stories have the power to normalise identities, challenge stereotypes, and foster empathy.

In a society negotiating rapidly shifting values, films like Maja Maa do more than entertain; they help build bridges between tradition and transformation. By centring love, humanity, and acceptance, the film becomes a meaningful piece of media advocacy that gently but firmly moves Indian cinema toward a more inclusive future.

Aishwarya Rajput is a media researcher and writer exploring the intersections of cinema, culture, and community narratives through an academic and creative lens.