Sinjini Ghose | 21st November 2025

In Bengal, each day seems like a celebration. Songs, customs, colors, cuisine, and traditions that bind people together across time and generations are the beating heart of West Bengal’s culture. The Bengali phrase “Baro Mase Tero Parbon” translates to “thirteen festivals in twelve months.” Here, festivals are more than simply occasions; they are feelings, a sense of self, and a way of life. Bengal’s friendliness, inclusivity, and cultural diversity make it a welcoming place for all.

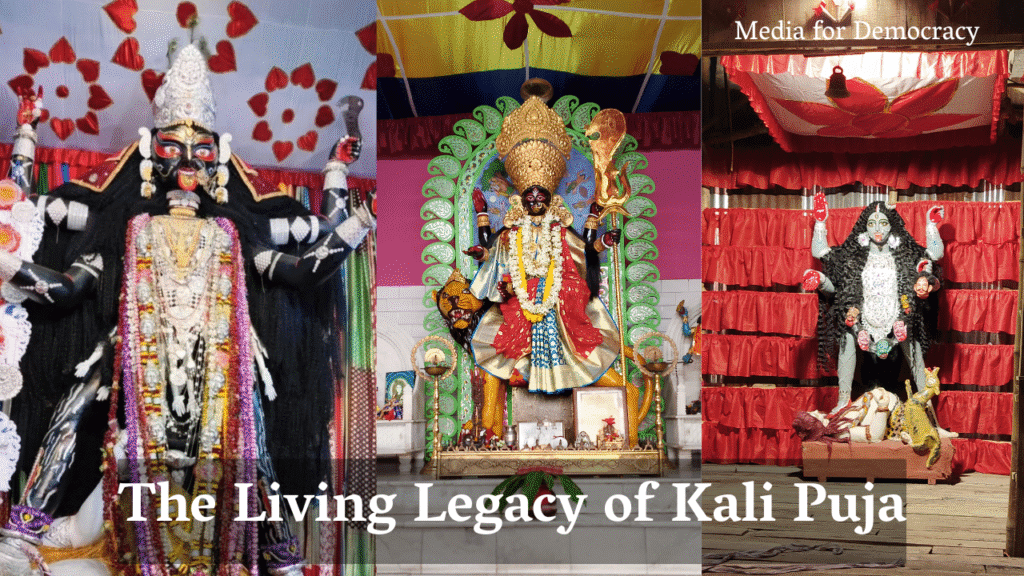

In Bengal, Diwali takes on a completely different divine significance as the night of Kali Puja, while the rest of India lights up the night with Diwali.

Here, Kali is more than simply a goddess; she is also time, death, destruction, mother, protector, cosmic wisdom, and freedom.

Origins and Growth of Kali Worship in Bengal

Kali Puja spread significantly throughout Bengal in the 18th century, especially under the patronage of influential figures such as King Krishna Chandra of Nadia. Later, in the 19th century, the devotion of Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansa elevated Kali worship even further among Bengal’s spiritual and cultural consciousness.

Zamindars of Bengal began organizing massive pujas, turning them into grand displays of devotion, wealth, and social prestige. That legacy continues today. Even now, while Diwali sparkles across India, Bengal immerses itself in the fierce, powerful, deeply emotional worship of Maa Kali.

Historically, the goddess — once perceived as a deity linked primarily with death and dark cosmic energy — instructed sages to worship her in forms that reflect feminine domesticity and motherly nurturing, resulting in varied and syncretic forms of worship across regions.

Detailed explanations of the Eight Main forms of Kali:

There are eight different forms of Kali: Dakshina Kali, which means “merciful and benevolent,” Siddhi Kali, which means “bestower of spiritual accomplishments,” Guhya Kali, which means “keeper of secret knowledge,” Sri Kali, which means “abundance,” Bhadra Kali, which means “auspicious and protective,” Chamunda Kali, which means “the slayer of the demons Chanda and Munda), Smasana Kali, which indicates detachment, and Mahakali, which is the ultimate form of power. From merci, hidden wisdom, and ultimate cosmic power to fierce destruction and protection, each form symbolizes a different facet of the goddess.

Famous Kali idols in Bengal –

- Bama Kali refers to a unique form of the goddess Kali, identified by her placing her left foot on Shiva’s chest, which symbolizes a reversal from the more common representation of her right foot on him. This form is associated with a famous and ancient tradition in Shantipur, West Bengal, known as the Bama Kali dance. During this ritualistic dance, a large idol of the goddess is carried on the shoulders of devotees and made to “dance” during the immersion procession, a centuries-old celebration of her fierce power. Devotees carry the idol and jump, making it appear as though the goddess herself is dancing.

- Naihati’s Boro Maa refers to the large, 22-foot-tall idol of Goddess Kali at the Boro Maa Kali Temple in Naihati, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal, a significant pilgrimage site known for its unique worship practices. The temple worships Kali as the fierce Raksha Kali or Shamshan Kali, and it is also a popular spot for the annual Kali Puja festival. The temple was built after a person was inspired to return to Naihati and create a massive idol of Goddess Kali. It is considered a highly spiritual place, with a history spanning over 100 years.

- The unique fire procession during the Kali Puja in the Boltola village (also referred to as Kurumba or Amadpur) of Burdwan involves the entire village plunging into darkness, with the path for the goddess’s immersion illuminated solely by thousands of flaming torches made of jute sticks. All electric lights in the village are switched off, creating a stark contrast and heightening the focus on the firelight. Villagers and devotees carry large, flaming torches made from jute sticks (known as “mashal” in Bengali) to light the way for the idol’s journey to the immersion spot. The procession is described as a powerful, electric, and intense experience, with the raw energy of the tradition making it feel like stepping back in time. The Kali idol is carried on the shoulders of devotees, who make it appear to dance during the procession amidst the chanting of hymns and the rhythmic beats of traditional drums (dhaak).

This specific, dramatic use of fire torches to light the immersion path in total darkness is a signature and centuries-old tradition of the Boltola Kali Puja in Burdwan that sets it apart from other Kali Puja celebrations.

- The Dakshineswar Kali Temple is a major center for Kali Puja, a festival celebrated in West Bengal and other parts of eastern India on the dark, moonless night of the month of [Kartika]. During Kali Puja, the temple, dedicated to Bhavatarini, an aspect of Goddess Kali, is beautifully illuminated and draws huge crowds for rituals like the havan (fire ritual). Kali Puja coincides with Diwali but is celebrated with distinct local traditions, particularly in Bengal.

- Kalighat temple is a sacred site dedicated to the Hindu goddess Kali, believed to be one of the 51 Shakti Peeths where Sati’s right toe fell. During Kali Puja, the festival honoring the goddess, devotees visit to worship, with rituals including daily prayers, aarti, and offerings of sweets, fruits, and flowers. The temple is a major pilgrimage destination, especially during major festivals like Kali Puja and Durga Puja, which are celebrated with great fervor.

- Ratanti Kali Puja: This puja is observed on the 14th day of the dark fortnight (Krishna Chaturdashi) in the Hindu month of Magha (usually January/February). It is considered highly auspicious and is one of the important amavasya (new moon) related Kali Pujas besides the main one during Diwali.

- Phalaharini Kali Puja: Celebrated on the new moon day (Amavasya) of the Bengali month of Jyeshta (usually May/June). The name “Phalaharini” means “remover of the fruits (results) of actions” or karma. Devotees worship this form of the goddess to be freed from sins and bad karma. This puja holds special significance in the Ramakrishna Math and Mission tradition, as Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa worshipped his wife Sarada Devi as the goddess Shodashi on this day.

- Kaushiki Amavasya Kali Puja: This puja is associated with the new moon day known as Kaushiki Amavasya. It is greatly linked to the goddess Tara of Tarapith. According to legends, it is believed that on this day, the goddess Tara appeared on Earth and blessed the saint Bamakhepa.

These various pujas highlight the diverse forms and significance of Goddess Kali across different times of the year and traditions within Hinduism.

Kali Puja in Bengal is not just worship — it is history, heritage, philosophy, identity, emotion, and an eternal spiritual connection. From Tantric mysticism to modern festive celebration, from cremation grounds to decorated pandals — Kali represents both ends of existence itself.

While the country celebrates Diwali with lamps of prosperity, Bengal celebrates the mother who destroys darkness itself.

And that is the essence of Bengal — fierce yet loving, rooted yet evolving, cultural yet cosmic.

Sinjini Ghose is an emerging cultural writer who explores India’s rich folk traditions, art practices, and storytelling heritage. Her work blends research with evocative narrative, bringing forgotten histories to life.