Aashish Gupta | 13th November 2025

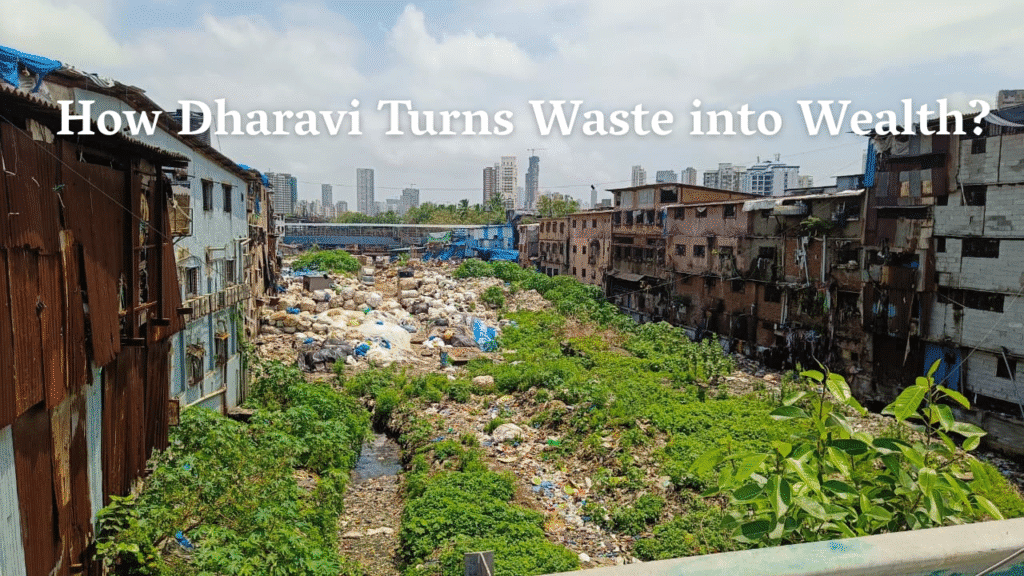

When people hear the word Dharavi, they often picture one of the biggest slums in Asia, with crowded lanes, small homes, and busy streets. However, hidden within those lanes is a vast recycling market that transforms Mumbai’s waste into something valuable. A visit to this area can be surprising and eye-opening. It reveals how thousands of people make a living by giving new life to the items others discard.

A World Made of Scrap

The main recycling area in Dharavi is called the 13th Compound. It consists of a maze of small lanes and tin-roofed sheds. Upon entering, visitors are met with the strong smell of melted plastic, oil, and metal. People are everywhere, sorting, cleaning, melting, and reshaping waste into items that can be resold. Large piles of bottles, plastic containers, metal wires, and cardboard occupy every corner. Machines produce loud grinding noises. Men and women move swiftly, knowing their tasks.

In one small workshop, broken plastic chairs and bottles are crushed into small pieces. These pieces are washed, dried in the sun, and melted into tiny pellets that can be reused in factories. In another lane, metal scraps are hammered and reshaped. Paper and cardboard are also collected, sorted, and packed neatly for sale. It’s hard to believe just how much work takes place in these small spaces, but every bit of waste here has a purpose.

How the Recycling System Works

Dharavi’s recycling efforts are significant. Experts estimate that this area handles about 80% of Mumbai’s recyclable waste, which includes plastics, glass, paper, and metal. Nearly 250,000 people are connected to this work in various ways—ragpickers, shop owners, factory workers, drivers, and traders.

Every morning, trucks and handcarts arrive with waste collected from homes, shops, and streets across the city. Scrap dealers buy the waste and bring it to Dharavi. Here, the waste goes through many steps—sorting, washing, shredding, melting, and finally selling to factories that produce new items. This is a clear example of a circular economy, where nothing goes to waste. However, this system mostly operates without government support or formal licenses. It relies on people’s skills, hard work, and connections.

A Difficult Welcome

The visit to Dharavi’s recycling lanes was challenging. Many workers were hesitant to talk or be filmed. When cameras appeared, some turned away while others firmly stated, “No photo, no video!” Initially, this reaction felt rude. However, it soon became clear why people behaved this way. Many of these small workshops are not officially registered. Workers fear that photos or videos might lead to problems. Others have encountered outsiders who only focus on the negative aspects of their work, ignoring their effort and skill.

Still, a few people opened up. One young man operating a plastic grinding machine said quietly, “This is hard work, but this is what feeds our families. People call it garbage work, but we are cleaning the city.” His words conveyed both pride and pain—pride in what he does, and pain that most people don’t respect it.

People and Their Work

Each lane in Dharavi’s recycling area buzzes with activity. In small workshops, three to five workers handle several tons of waste each day. Most work long hours, often from early morning until night. Watching them is like observing a well-trained team. They can identify different types of plastic by touch. They know which bottles can be melted together and which must be sorted separately. Nothing is wasted—even broken tools are repaired and reused.

By evening, the morning’s waste is already transformed—sorted, cleaned, and ready to be sold. Traders then transport it to factories in other parts of the city or even to other states. There, it becomes new buckets, toys, or containers. It’s hard to believe that the clean plastic products used daily may have begun as waste in Dharavi.

The Hard Reality

While the work is admirable, it is also very tough. The heat inside the small sheds is intense, and the air is filled with chemical smells. Most workers lack safety gear—no gloves, no masks. They handle sharp objects, dirty waste, and hot machines with bare hands.

Women work alongside men, often washing plastic flakes in large tubs of dirty water. Children play near piles of plastic and metal. Many workers live in small rooms close to their workshops. Doctors and environmentalists have raised concerns about health issues from plastic dust and toxic fumes. The water used for washing waste often flows into drains, polluting nearby areas. Yet, for many here, this is the only way to earn a living. “Work is work,” one woman remarked. “If we stop, who will feed our families?”

Uncertain Future

Now, Dharavi’s recycling world faces an uncertain future. The government’s new redevelopment project plans to rebuild large parts of the area. Many fear this will destroy their small workshops or move them away from their suppliers and customers.

There’s another issue—the global market. When oil prices drop, virgin plastic becomes cheaper, leading factories to stop buying recycled plastic. This can slow business and reduce workers’ income. Despite these challenges, recycling in Dharavi continues. The people here don’t give up easily. Every day, they demonstrate that waste can turn into something valuable, and that work and hope can thrive even in the toughest conditions.

The Real Lesson

As I left the 13th Compound, the noise of machines faded, replaced by the usual city sounds—cars, horns, and conversations. However, the images lingered—people covered in sweat and dust, tirelessly working to turn garbage into something useful.

To outsiders, Dharavi often seems like a place of poverty. Yet for those who live and work there, it is a realm of skill, strength, and resilience. This recycling world is one of Mumbai’s silent engines. It keeps the city cleaner, offers work to thousands, and proves that sustainability doesn’t always rely on large companies or government plans. Sometimes, it arises from ordinary people doing extraordinary work with very little.

Dharavi may appear rough and unwelcoming to visitors. But within its narrow lanes, people are doing something powerful—they are giving value to what others discard and reminding everyone that no work is insignificant when it helps a city become cleaner and better.

Aashish Gupta is a writer focusing on culture, communities, and socio-economic issues, bringing attention to the people and places often overlooked in mainstream narratives.