Divyansh Kabeer | 23rd November 2025

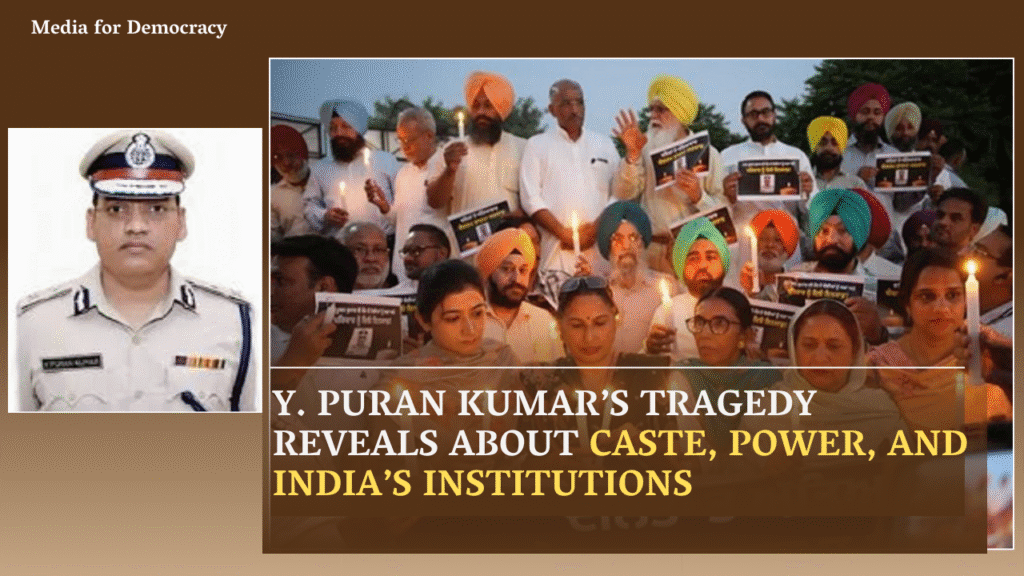

On 7 October 2025, the quiet lanes of Chandigarh’s Sector II were shattered by a tragedy that continues to send ripples through India’s administrative and policing systems. Y. Puran Kumar, a 52-year-old Haryana-cadre IPS officer and Additional Director General of Police, was found dead in the soundproof basement of his government residence. His teenage daughter discovered him. A handwritten nine-page note and a sign will lay nearby. The incident shocked the country, but the conversations it has reopened are far older—and far more uncomfortable—than one man’s death.

Although the investigation is ongoing, and the allegations mentioned in his suicide note remain to be proven in court, the case has forced the public to confront a long-standing question: How deeply does caste discrimination continue to operate within the country’s most powerful institutions?

This is not simply a story of a senior police officer who died by suicide. It is a story of what India asks of its Dalit officers, how it treats them when they speak up, and what happens when the burden of silence becomes too heavy.

The Life of an Officer Who Refused to Stay Silent

Puran Kumar came from a Scheduled Caste background and built his career through grit, academic excellence, and a reputation for service. But he was also known as someone who regularly challenged caste-based discrimination within the police force. He returned to his official vehicle when he felt singled out, filed formal complaints alleging harassment by senior officers, and approached courts over what he described as irregular promotions. Few officers of his rank openly articulate such grievances; even fewer continue to do so for years.

Just a day before his death, a separate police case in Rohtak suddenly brought unwanted attention to his name, after a constable was arrested for allegedly demanding a bribe while wrongly invoking Kumar’s authority. Though Kumar was neither accused nor summoned, the incident reportedly added to the pressures he already felt.

According to the FIR later filed by Chandigarh Police, based on the complaint by his wife, senior IAS officer Amneet P. Kumar, the suicide note names senior police officials and alleges caste-based harassment and administrative victimisation. The FIR includes provisions related to abetment of suicide and the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. The investigation will determine the veracity of these claims, but the themes they raise have long resonated within Dalit communities.

The Issue: Caste Inside ‘Modern’ Institutions

For many, this case is a stark reminder that caste discrimination does not end at the gates of elite academies, civil services, or high-rank offices. It shapeshifts. It hides behind “discipline,” “hierarchy,” “fitness,” or “merit.” It wears a uniform.

Dalit officers across India have often spoken—sometimes anonymously, sometimes fearlessly—about being sidelined from prestigious postings, facing targeted inquiries, or being given “punishment transfers.” The tragedy of Puran Kumar’s death echoes earlier institutional tragedies linked to caste hostility: the deaths of Rohith Vemula, Dr. Payal Tadvi, and Darshan Solanki. Though the circumstances differ, a common thread binds them: the experience of marginalisation within spaces that promise equality but often fail to deliver it.

Caste does not need slurs to survive; it thrives in structures.

Why This Matters

This case is not about disproving or confirming every line in the note. That is the task of investigators and courts. What matters—and what is undeniable—is that the death of a senior Dalit IPS officer has created a sense of collective anguish, particularly among those who see the system from the margins.

Three questions stand out:

1. What does it say about our institutions when even top officers feel unheard or unsupported?

2. What mental-health mechanisms exist for high-stress services like the police, where vulnerability is often treated as weakness?

3. Why does caste still shape opportunities, experiences, and dignity in settings built to serve a democratic, constitutional republic?

These are not rhetorical questions. They demand answers.

The Human Cost of Silence

The police force is one of the most stressful professions in India. Officers routinely witness violence, face political pressure, and work in hierarchies where disobedience—real or perceived—can end careers. For Dalit officers who face additional biases, the stress compounds.

The stigma around mental health in uniformed services is severe. Seeking help is often equated with being “unfit” or “unstable.” The result is predictable: people suffer in silence.

Had a workplace counselling mechanism existed—staffed by independent professionals rather than internal officers—could the outcome have been different? Perhaps. What is certain is that too many public servants navigate emotional and psychological crises alone, with no institutional safety net.

The Matter Before the State

The FIR filed on the basis of Amneet Kumar’s complaint marks the beginning of a legal process. It lists senior officials, including the Haryana DGP and a district SP, for investigation under abetment and SC/ST Act provisions. Those named deserve a fair and transparent inquiry, and no conclusion should be drawn before evidence is examined.

Yet the existence of the complaint itself reflects the magnitude of the trust deficit between Dalit officers and the institutions meant to protect them. Trust frays not only when discrimination occurs, but also when justice mechanisms feel inaccessible or ineffective.

If a senior IAS officer must fight this hard for an FIR, what hope remains for those with less institutional power?

A Way Forward: What Needs to Change

The tragedy of Puran Kumar’s death should not become just another headline. It should be a turning point.

1. Independent and time-bound investigation: A swift, transparent, and impartial inquiry—possibly monitored by bodies like the National Commission for Scheduled Castes—can restore faith and prevent the case from becoming politicised or buried.

2. Institutional mechanisms against caste discrimination: Every police and administrative service must create: independent grievance redressal bodies,anonymous reporting channels,mandatory sensitisation programmes led by Dalit scholars and officers.

Committees that include members only from dominant groups cannot be trusted to handle caste grievances.

3. Mental health support for officers: Counsellors must be posted in every training centre and major department. Officers should be able to seek help without fear of stigma or career damage.

4. Cultural reform : Institutions must understand that caste bias is not always overt. It lives in tone, postings, joking culture, and evaluation. Changing structures without changing mindsets leads nowhere.

The System Must Answer

The death of Y. Puran Kumar is a personal tragedy for his family. But it is also a national moment of reckoning. It questions the integrity of institutions that claim equality but often reproduce the inequalities of the society around them.

Justice for him—whatever the investigations reveal—will not be complete until India confronts the invisible architecture of caste that shapes everyday life, even within its highest offices. It will not be complete until Dalit officers can serve without fear of humiliation or exclusion. And it will not be complete until institutions recognise that dignity is not a privilege bestowed by rank, but a right guaranteed by the Constitution.

A society is measured not by how it treats the powerful, but by how it treats those it has historically wronged. In remembering Puran Kumar, India must decide what kind of society it wants to be.

Divyansh Kabeer is a Delhi-based writer who focuses on social justice, caste, and urban inequality. Through human-centered narratives, he highlights the invisible struggles of marginalized communities and their fight for dignity.