Navya Kalesan | 31st August 2025

On paper, Mumbai University stands as a towering institution of prestige — one of the largest university systems in the world, educating over 650,000 students. In 2024 alone, nearly 80,000 of its 152,000 graduates were women. But for the thousands of young women who walk its hallways, the most basic dignity is often compromised.

Yet, for thousands of female students, this commitment feels like an illusion. Behind the grand lecture halls and convocation ceremonies, the daily reality is stark: broken sanitary pad dispensers, closed or inaccessible washrooms, and an absence of disposal facilities.

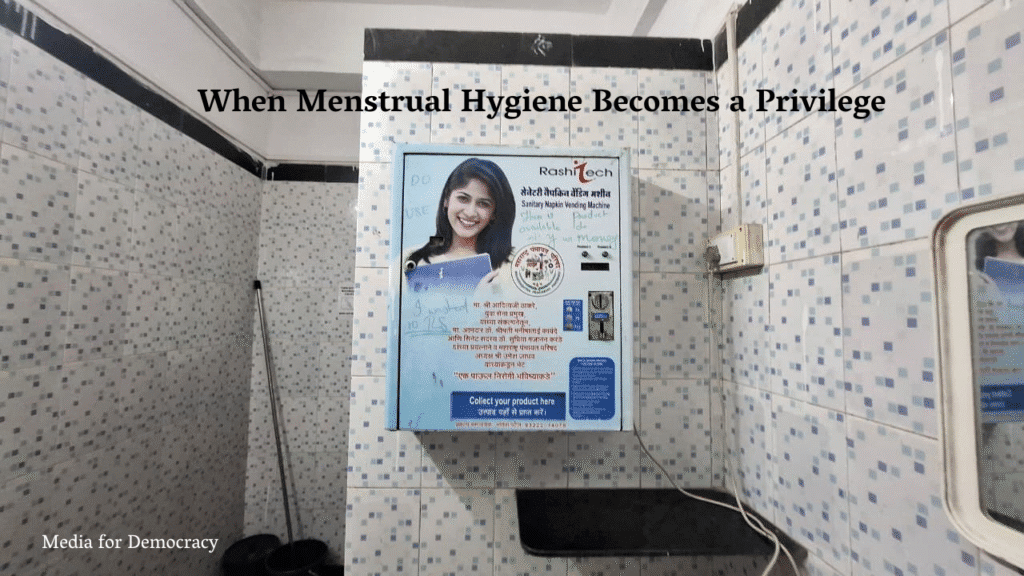

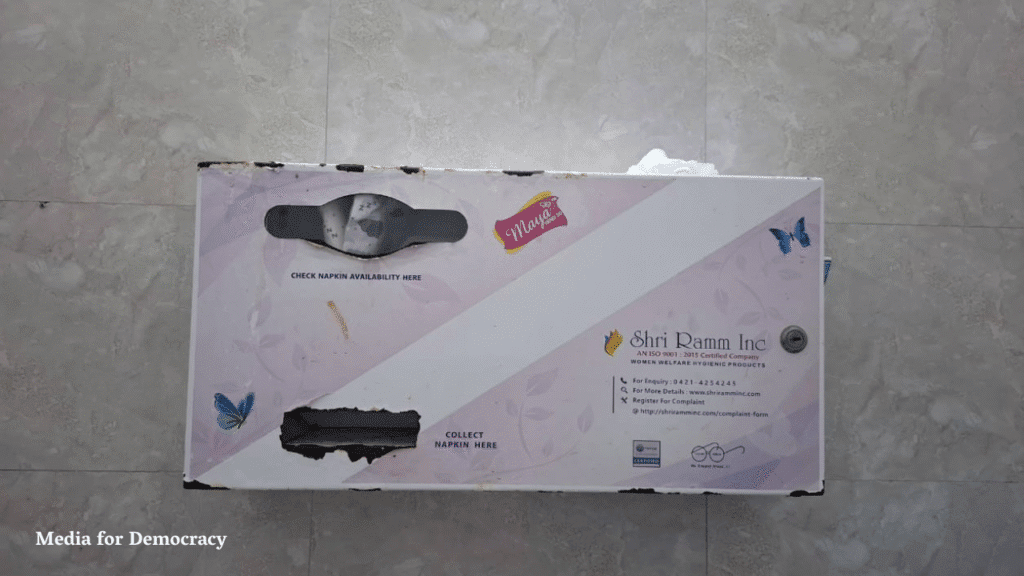

Machines That Don’t Work

Over the years, the University of Mumbai has installed sanitary napkin vending machines in a few departments.

But a walk across Kalina campus tells a different story. In most departments, the machines are not just empty; they are broken, rusted, or reduced to the status of wall décor. Students recall that in most places, the machines have not been functional for months, and no authorised official has taken notice of their upkeep.

The Department of English, for example, has a machine that remains perpetually non-functional. The Department of Linguistics has one, but it has been left to rust. In the Health Centre building, where menstrual support should be most available, the vending machine has become totally non-functional.

Health Centre Building

The conditions in some other departments are far worse. History, Persian, French, Commerce, Sociology, and even the department of Eurasian Studies lack the facility altogether. For women across these spaces, menses remains a silent problem.

“We usually carry our own sanitary napkins because these machines never work,” said Shreyasi Karapu, an MA Part 2 student, to Free Press Journal.

It is a simple statement, but it captures the core of the problem. Machines were installed with enthusiasm. Maintenance never followed.

Scarcity in Numbers

When placed against the scale of Mumbai University, the inadequacy becomes even more stark. In 2024, nearly 80,000 of the university’s graduates were women. Add to this the thousands of female students enrolled in postgraduate programs, research, and professional courses, and the scarcity of working dispensers becomes indefensible.

The number of sanitary napkin vending machines in relation to the number of female students is worryingly low. Even if a few machines on the campus are working, they will not be able to cater to everyone. With the vast majority of them being empty as well as non-functional, the gap between demand and supply is massive.

No Space for Disposal

For those who manage to bring their own pads, a new challenge begins to take shape: the absence of suitable disposal facilities. Pad-friendly dustbins are not in abundance in many washrooms across the campus. To a large extent, students end up carrying their used pads in search of a bin, which means having to travel across corridors to get rid of them.

This is certainly more than a mere inconvenience. It poses a health risk and is a disrespect to dignity. Such an essential aspect of a woman’s life cannot continue to be ignored by a university that prides itself on being a leading institution.

The Role of the Women’s Development Cell

The Women’s Development Cell (WDC) of Mumbai University was created in 2001 with the aim of building a gender-sensitive campus. Its vision speaks of independence, safety, dignity, and equitable opportunities for women. It has also taken on the responsibility of gender sensitization, rights awareness, and well-being for female students and staff.

The mission statements and objectives are determined: preventing sexual harassment, promoting empowerment, conducting gender audits, and creating inclusive spaces. Yet, when it comes to menstrual hygiene, the silence is striking.

The WDC is well placed to lead change. A functional, well-maintained menstrual hygiene infrastructure across departments could be one of the most immediate and visible signs of the university’s commitment to women’s dignity. But without commitment, the gap between the WDC’s vision and the lived reality of students will continue to widen.

A Daily Struggle for Students

The absence of consistent menstrual support services has normalized a culture of self-adjustment among women students. Many carry extra supplies in their bags at all times, and others rely on friends or leave campus when emergencies strike.

The lack of dustbins inside the washrooms forces students to hide used pads in their bags until they can find a disposal point. Such experiences are rarely spoken about publicly, but they weigh heavily on students’ daily experience of university life.

More Than a Hygiene Issue

It would be a mistake to dismiss this as a matter of accessibility. Menstrual hygiene is a matter of health, equity, and participation. When women are denied safe, hygienic, and self-respecting spaces to manage their periods, their access to education itself is undermined.

This crisis is also an issue of silence. Students often say there is no point in raising complaints because nothing changes. When vending machines remain empty month after month, when bins remain missing year after year, women learn to adapt rather than demand. This normalization of neglect is perhaps the most dangerous outcome of all.

What Needs to Change

- All existing vending machines must be repaired, restocked regularly, and monitored for functionality.

- The current allocation of machines is totally insufficient. Each department must have multiple working machines proportional to the number of students and staff.

- Every woman’s washroom must have a clean dustbin dedicated to menstrual waste along with simple, visible instructions on its usage.

- The Maintenance team or hired contractors must be given responsibility to do periodic checks and proper maintenance.

Toward a Gender-Sensitive Campus

Mumbai University is one of India’s most notable educational spaces. But respect cannot be measured only in convocation halls or academic rankings. It is equally reflected in whether a young woman can walk into a washroom and find dignity, safety, and care.

The menstrual hygiene crisis on campus is not about broken machines alone. It is about an institution’s readiness to recognize and respect the lived realities of half its student population. Until vending machines work, until bins are placed, until women no longer carry their own supplies in anticipation of neglect, the promise of a gender-sensitive campus will remain dull.

For a university that prides itself on shaping futures, there is no excuse for failing at such a basic responsibility. The Women Development Cell, administration, and student community must together ensure that menstrual dignity is no longer left outside the washroom door.

Navya Kalesan is a media researcher whose work focuses on student welfare, policy gaps, and campus experiences in higher education. She writes critically on how institutional promises often diverge from everyday realities.