Pushpa Gajabe | 20th August 2025

Stray dogs are part of Mumbai’s everyday life. From curling up under tea stalls to following familiar feeders across lanes, they are woven into the city’s fabric. For many, they are companions, not nuisances. Yet their existence has been thrown into uncertainty after the Supreme Court’s recent order directing the removal of all stray dogs from Delhi-NCR within eight weeks.

The ruling has left animal lovers, feeders, and pet parents across India — especially in Mumbai — deeply concerned. Beyond the legal language, the question is simple: what will happen to the thousands of voiceless animals who rely on human compassion for survival?

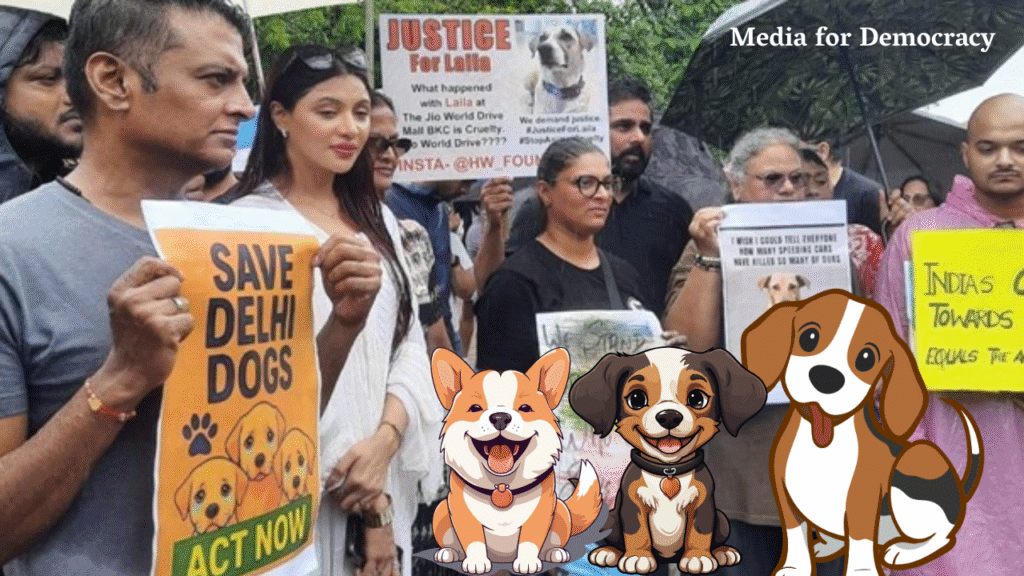

On a cloudy evening in Bandra, dozens of animal lovers gathered to be “the voice of the voiceless.” The meeting wasn’t just about policy; it was about empathy. People who feed, foster, and care for community dogs came together to question the hurried timeline and demand humane alternatives. It was here that I spoke with a range of voices, from everyday citizens to well-known public figures, each united in concern.

A Citizen’s Concern

Sasha Rometra, a 26-year-old Mumbai resident, has lived with both an indie dog and a cat. But because of her mobile lifestyle, she now focuses on fostering and feeding community animals. For her, the issue is deeply personal.

She acknowledged the seriousness of rabies and bite cases but questioned whether the court’s order offered a workable solution. “An eight-week timeline for removing street dogs is simply unrealistic,” she said. Instead, she argued for long-term solutions like sterilisation, vaccination, and planned shelters.

Her worry was not just about feasibility but also about consequences. Rushed implementation, she warned, could lead to dog dumping, corruption, overcrowded shelters, and starvation. “This isn’t just about opinions; it’s also about values. Humane government policy is non-negotiable,” she concluded.

Her words underline the gap between courtroom directives and ground realities.

Actor Sumeet Raghavan, who joined the Bandra gathering, shared similar concerns. Speaking with both frustration and hope, he called the ruling a “knee-jerk reaction by the Honourable Supreme Court.”

“I understand there are two sides to every coin,” he said. “But we cannot sit in our high chairs and dictate terms. We need to meet, talk, and find an amicable solution. Yes, public health and safety matter, but so does the safety of the dogs.”

Raghavan highlighted the sheer impracticality of the ruling. “Just rounding up three or ten lakh dogs and putting them in pounds will not solve anything. It’s not even possible. It is unfair.”

His words were echoed by many present, who believe that India’s cultural and ethical values leave no space for cruelty against animals.

Learning from the Past

Another participant, Abeez, reminded the gathering that India has already seen failed approaches. During the British era, stray dogs were simply euthanised. After Independence, NGOs realised that neither killing nor relocating worked because dogs are territorial. Remove them, and others simply move in.

Instead, spaying, neutering, vaccinating, and returning dogs to their original territory became the recommended model. This approach, though slow, has proven effective.

But Abeez expressed scepticism about current government shelter proposals, fearing that the rhetoric of “rehabilitation” could mask large-scale euthanasia. Transparency, he stressed, is key. Without it, trust is impossible.

Need to Recheck Gaps in Policy

For Sunita, another animal welfare advocate, the frustration lay in what wasn’t done years ago. She pointed out that sterilisation and vaccination programs, mandated by law, should have been fully implemented a decade earlier.

She identified two urgent challenges: population control and feeding management. Dogs, she argued, cannot be wished away; their hunger is real, and when ignored, it leads to aggression.

Sunita also dismantled common myths. Not every dog bite results in rabies, she said, and NGOs are willing to help but lack proper funding and government support. She questioned the feasibility of mass relocation without infrastructure, pointing to the problems that already plague cow shelters. “Inhumane treatment of voiceless animals is not a solution. We would never deal with human issues this way — why should it be acceptable for animals?”

Beyond the Courtroom: What This Debate Really Means

Taken together, these voices from Mumbai highlight a simple truth: this issue is not about being “pro-dog” or “anti-dog.” It is about what kind of society we want to be.

Yes, public safety is a real concern. Dog bite cases and rabies must be addressed. But cruelty, shortcuts, or mass relocation will only deepen the crisis. Sterilisation, vaccination, and responsible feeding programs may be slower and costlier, but they are the only humane and sustainable path forward.

The Supreme Court’s ruling has opened an urgent debate, but Mumbai’s response offers hope. Citizens, feeders, and even public figures are demanding not just quick fixes, but compassionate, long-term solutions.

Stray dogs are not intruders in our cities; they are part of our shared spaces, our communities, and, for many, our lives. To treat them as disposable is to betray the very values of empathy and coexistence that India prides itself on.

In the end, how we choose to treat the most vulnerable — even voiceless street dogs — will decide what kind of society we truly are.

Pushpa Gajabe is a media researcher with a keen interest in society, culture, and communication. She writes on issues of public concern, highlighting voices often left unheard and exploring the role of media in shaping narratives.