Krutika Jadhav | 31st August 2025

Mumbai University is a place where thousands of students arrive each year, carrying dreams of careers, independence, and a brighter future. Its sprawling campus, buzzing corridors, and historical importance make it a place where ambitions take flight. But for students with disabilities, this promise is often tempered by daily reminders that their presence was never fully considered.

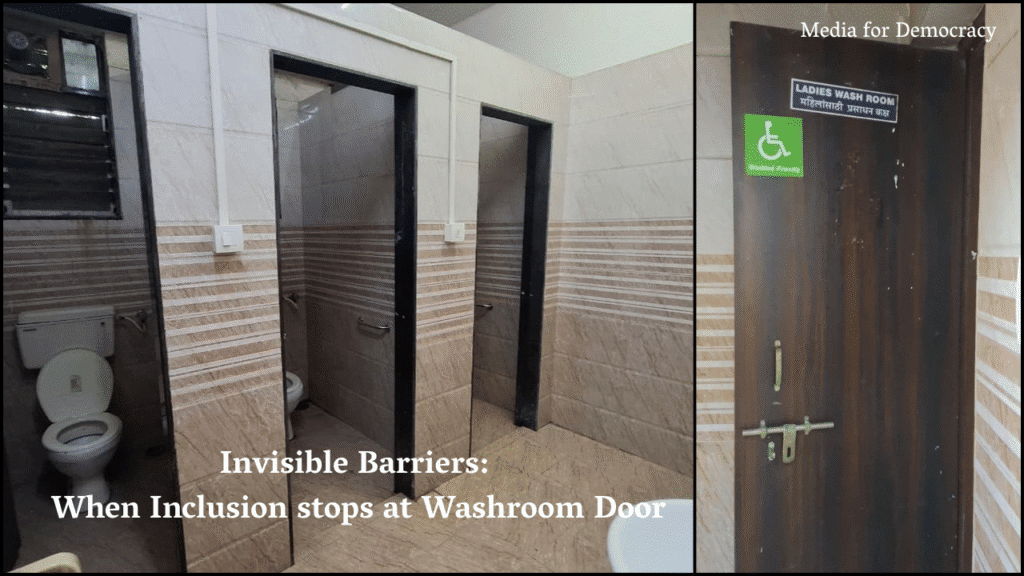

What should be a site of equal opportunity often becomes a site of silent exclusion—not always in classrooms or libraries, but in the most ordinary of spaces. Washrooms, facilities so basic that most students barely think twice before using them, stand out as markers of this neglect. For many disabled students, entering a washroom is not a simple matter of convenience; it is a matter of dignity and safety.

No ramps, locked or non-functional “accessible” stalls, narrow doorways, and the absence of support bars transform a routine bodily need into a challenge filled with anxiety. These physical barriers are joined by emotional ones: the embarrassment of asking for help, the guilt of leaving class early. In these corners of the campus, the ideals of equity and inclusion quickly unravel.

Silent Exclusions

The university has made improvements in many areas. New lecture halls boast air-conditioned classrooms, sprawling libraries are stocked with millions of books, and digital boards reflect the institution’s attempt to modernize. But tucked away at the back of buildings, washrooms tell a different story.

Many are inaccessible to wheelchair users because of narrow doors or steps without ramps. Some washrooms are even converted into storage spaces or locked without explanation. For students with visual impairments, slippery floors and the lack of tactile cues turn these spaces into dangerous zones.

The absence of basic infrastructure forces students with mobility challenges into exhausting compromises. Instead of focusing on lectures, research, or friendships, their days are structured around coping strategies—limiting water intake to avoid bathroom visits, timing meals carefully, or leaving campus early when facilities are unusable. What ought to be a universal human right becomes a source of constant anxiety and physical strain.

Hygiene as Health

The problem extends beyond physical access. Cleanliness and hygiene in the few available washrooms are inconsistent at best. Floors are often wet and slippery, flushes remain broken, and soap dispensers are nowhere to be found. For students with disabilities, these lapses pose a greater risk than mere inconvenience. Slippery tiles threaten falls, and the lack of proper sanitary disposal facilities forces many to rely on unhygienic alternatives.

Health consequences quietly emerge in this environment. Students who avoid washrooms altogether risk dehydration and urinary tract infections. Those who attempt to use unsafe facilities face heightened chances of injury. The absence of menstrual hygiene facilities in accessible washrooms adds another layer of exclusion, leaving disabled students who menstruate without privacy or dignity in managing basic needs.

An Emotional Burden

Accessibility is not only about ramps and rails; it is also about emotional security. Every locked door or unusable washroom sends an unspoken message that the needs of disabled students are peripheral. The constant effort to adapt in silence builds a heavy emotional toll.

Instead of experiencing the campus as a place of inclusion, many students internalize feelings of isolation and invisibility. This emotional strain seeps into academic life as well. Students shorten their campus hours, withdraw from extracurricular activities, or hesitate to participate fully in group work. The inability to access something as ordinary as a washroom becomes a barrier to accessing the full spirit of university life. In these moments, the institution’s promise of equal opportunity feels empty.

The Policy Gap

The irony of this neglect lies in the legal framework that already exists. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, clearly mandates barrier-free access in educational institutions, including proper washroom facilities. Circulars from the University Grants Commission reiterate this responsibility, urging universities to ensure inclusivity beyond classrooms. Yet the gap between policy and practice remains wide.

At Mumbai University, accessibility is often treated as a token gesture. A single ramp at a building’s entrance or a lone “disabled-friendly” stall per department is presented as sufficient, regardless of whether it is functional or well-maintained. The excuse of “old infrastructure” is frequently cited, but this argument collapses in the face of years of unfulfilled promises and slow progress. True accessibility requires more than symbolic additions—it requires accountability.

The Normalization of Neglect

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of this issue is how normalized it has become. Students with disabilities quietly adjust their routines, accept inadequate facilities, and expect little improvement. Complaints rarely translate into change, reinforcing a cycle of neglect. Over time, these lowered expectations allow the administration to avoid accountability.

What should be recognized as a violation of rights is instead absorbed into a culture of “managing somehow.” This normalization of neglect reflects not only infrastructural gaps but also attitudinal ones. Accessibility is too often framed as charity—something “nice to have” if resources permit—rather than as a right embedded in human dignity. This mindset ensures that even well-intentioned interventions remain half-hearted, failing to address the depth of the problem.

Toward Real Inclusion

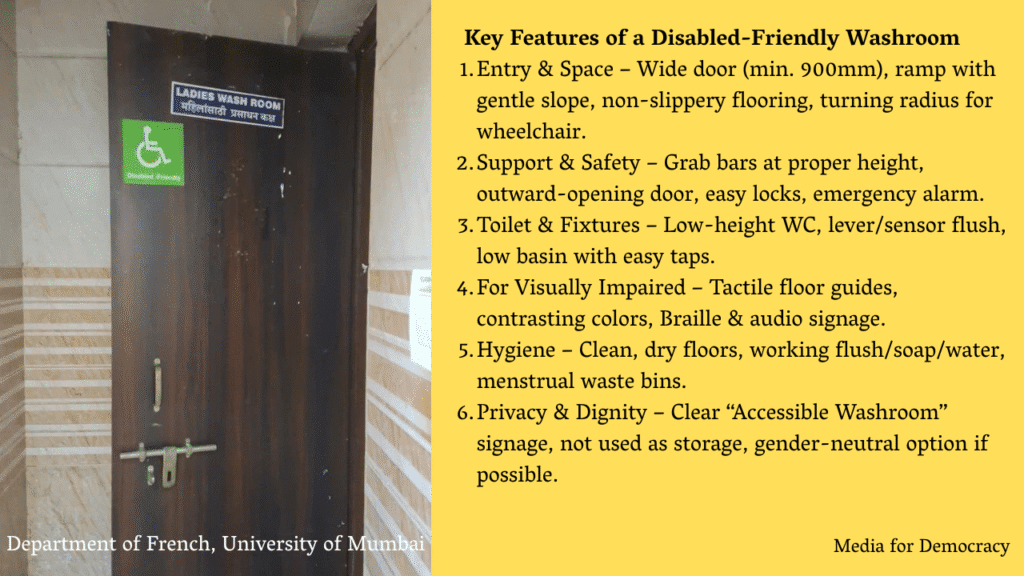

The way forward is not impossible. It requires an honest commitment to equity. Every academic building must house at least one fully functional, accessible washroom that remains open and clean throughout the day. These must include wide doors, ramps with proper gradients, working grab bars, low sinks, tactile indicators for visually impaired students, and menstrual waste disposal facilities.

Regular maintenance schedules must be enforced, and accountability must be established for lapses. Beyond infrastructure, the planning process itself must change. Students with disabilities should be included in reviewing and designing facilities. Their lived experience is the most reliable guide to creating systems that work. Additionally, training programs for maintenance staff can ensure that accessible washrooms remain functional, clean, and safe over time.

Dignity in the Everyday

At its core, this is not merely an issue of toilets and tiles. It is about dignity. A university cannot claim inclusivity while students must ration water, cut short their campus hours, or feel unsafe in basic facilities. A place of learning should empower students to thrive in every aspect of their lives, not remind them daily of their limitations.

Mumbai University, with its stature and resources, has the potential to set a national example in accessibility. But until it takes responsibility for the ordinary needs of its disabled students, its reputation will remain undercut by a quiet but powerful truth: that inclusion promised in speeches and policies does not extend into the most fundamental spaces of daily life.

Krutika Jadhav is a media educator and storyteller who amplifies everyday struggles and gendered realities often overlooked in public discourse.