Arnesh. P | 27 June 2025

On the hot summer afternoon of June 2, Ambernath railway station in the state of Maharashtra witnessed not only a shocking event but also a heart-warming display of human bravery. Siddhanath Mane, a visually impaired passenger, lost his footing and ended up on the railway track just as a local train was rushing onto the platform. What came next was an act of valour and a fantastic display of collective action.

The viral CCTV footage records the whole incident in detail. While the visually impaired man struggles in vain on the tracks, MSF jawan Amol Deore, who is present in the vicinity, doesn’t lose any time. He climbs onto the tracks, putting his own life at risk, and gestures to the train driver with wild arm movements. His quick thinking makes other commuters spring into action. The train is brought to a stop just in time. The blind man was rescued from the tracks, shaken but alive.

What could have so easily culminated in disaster instead initiated an explosion of virtual cheers. The video has gone viral, with Deore being celebrated as a true hero. But behind the cheers is one serious question: Why did this occur in the first place?

Where Were the Safety Measures?

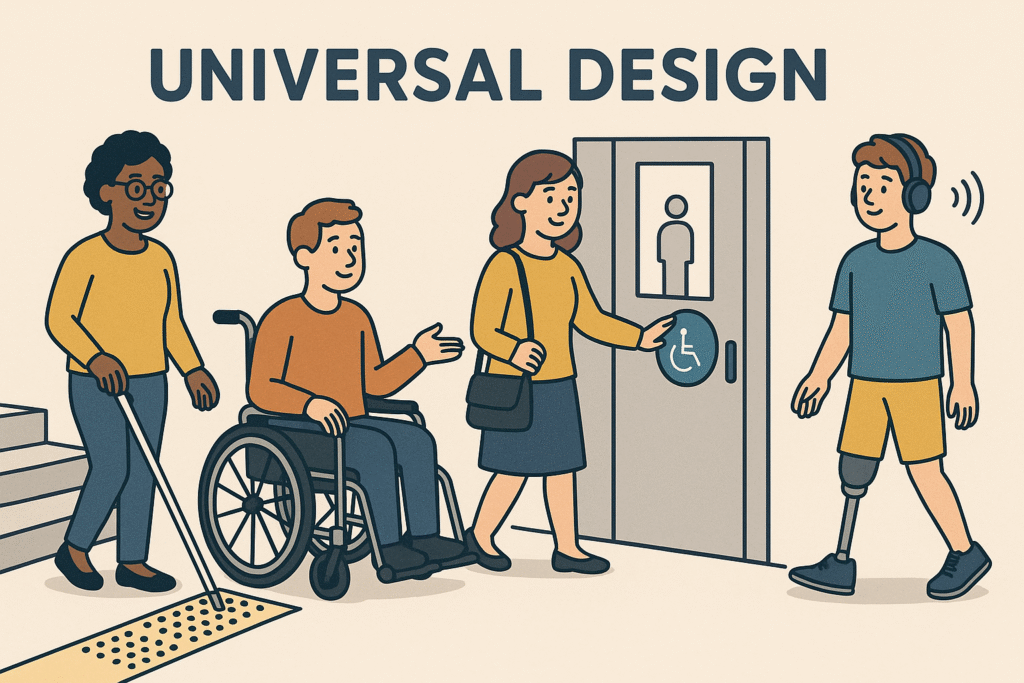

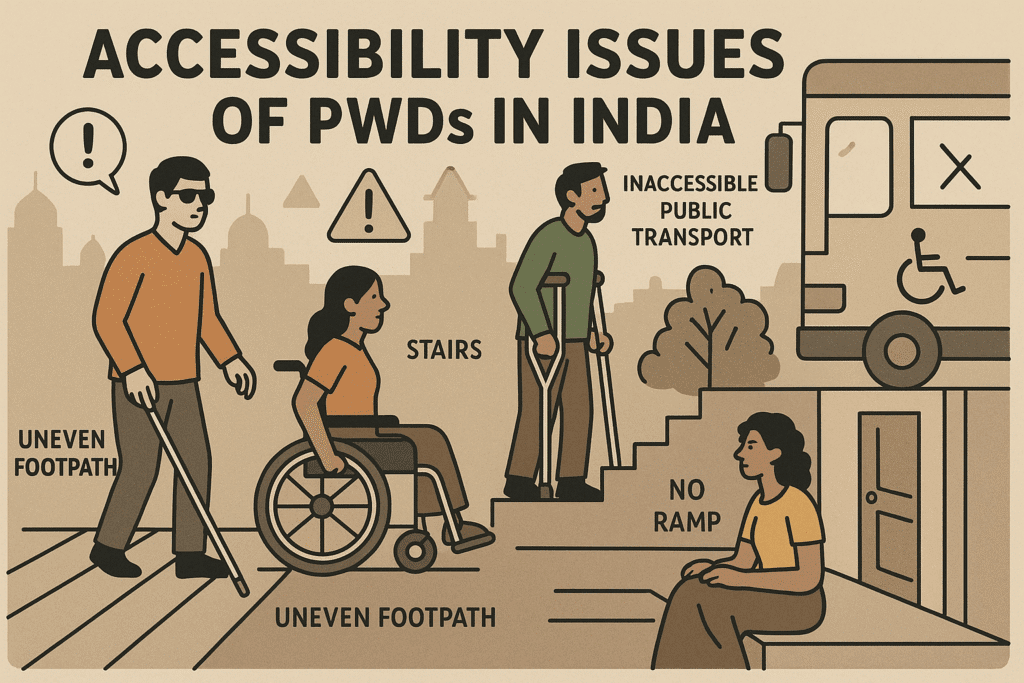

Ambernath station, like several others in India, does not have minimum accessibility facilities for individuals with disabilities. Most importantly, the platform didn’t have tactile markings, the raised, texturized strips on floors that are meant to take visually impaired individuals safely from one point to another. These markings aren’t suggestions; they’re compulsory under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act, 2016, which explicitly declares that public infrastructure has to be accessible to everyone, particularly the differently abled.

According to the Harmonised Guidelines and Standards for Universal Accessibility, Indian Railways is legally required to provide such features as:

- Tactile paving to access train doors

- Platform-edge warning

- Audio announcements and display signs

- Ramps and handrails

- Disability assistance desks

But in practice, the majority of suburban stations particularly those on the Central and Harbour lines, lack such accessibility facilities miserably. As Shital Gamre notes in her research on Enhancing Accessibility on Mumbai Local Railways for Persons with Disabilities,

“Despite India’s legislative frameworks like the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, which advocate for barrier-free environments, the real-world implementation on public transport systems like the Mumbai local railways is still evolving.”

What More Can Be Done?

Whereas the human reaction at Ambernath was exemplary, the infrastructural and system reaction is missing. Some of the recommendations to prevent such incidents are:

- Platform-edge fences or barriers to avoid accidental falls.

- Infrared or motion sensors which give warning to staff when a person falls on the tracks.

- Special RPF or MSF staff on every platform, trained especially to help people with disabilities.

- Compulsory tactile indicators, with periodic audits for maintenance.

- Intelligent apps or wearable technology to guide visually impaired passengers through railway environments securely.

These are not future developments many are already being used at contemporary metro stations and airports. The challenge is in using them in suburban and rural railway stations where most of the daily commuters pass through.

The Law is Clear but is the System Listening?

Under the RPwD Act, 2016, Section 45 and 46, both government and private infrastructure providers are under an obligation to make the transport system accessible within a notified timeframe. The Act also has provisions for penalties in case of non-adherence, and gives powers to persons with disabilities to approach State Commissioners for redressal.

However, with or without legal clarity, enforcement is still patchy, without daily audits, activism from disability rights groups, and effective enforcement, these provisions might remain only on paper.

A Moment of Courage and a Call to Action

Amol Deore’s bravery rescued a life. But real development will be when such bravery is unnecessary when our public spaces are safe by design, not by accident. As Siddhanath Mane was saved, his brush with death should not be merely a viral video recollection. It should act as an eye-opener for policy-makers, railway officials, and citizens that accessibility is not an optional Infrastructure aspect but a mandatory one.

It is a lawfully right and a moral obligation. As Shital Gamre rightly puts it, “Accessibility in public transport is not a privilege, it is a right.” Local trains are the lifeline of Mumbai. Let’s make sure they are safe and accessible for everyone and not a place where one gap in infrastructure leads to tragedy.

Local trains are the lifeline of the Mumbai. Let’s make sure they are safe and accessible for everyone and not a place where one gap in infrastructure leads to tragedy.