Prajakta Kadam and Chatura Juwatkar

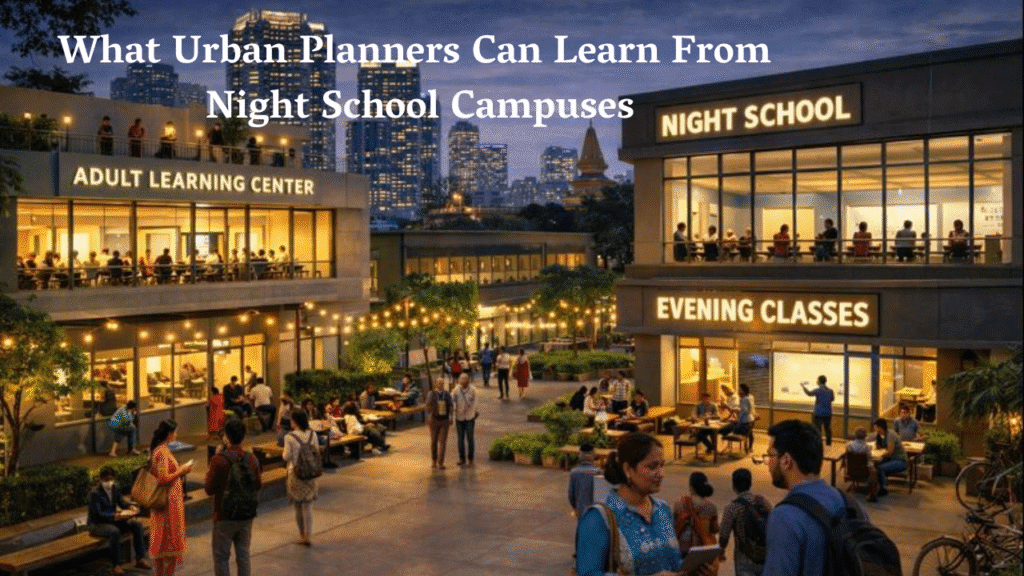

When the city winds down and shutters roll down on markets, another kind of shift begins in its quieter corners: adults take off uniforms, drop off tiffin carriers, wipe the dust off their faces and walk into night schools. Our field visits showed again and again that whether these learners can reach the classroom safely, arrive on time and return home without fear has less to do with motivation and more to do with how the city itself is designed. In other words, the urban plan is quietly deciding who gets to learn after dark.

The street as the first classroom gate

The journey to night school starts long before the campus gate. For most learners, especially women and young workers, the first obstacle is the street outside their home. Poor lighting, broken pavements, dark underpasses, and desolate bus stops act like invisible “No Entry” signs after 6 PM. In neighbourhoods where a single working streetlight or a busy tea stall sits at the right corner, attendance spikes; where alleys are narrow and deserted, parents and spouses are far more likely to say no.

These can be learning corridors, not just traffic infrastructure. That means planning continuous, well-lit walking and cycling paths between residential clusters and key learning hubs; placing bus stops and auto stands within visible, active frontages; and ensuring that any major night school or college operating after hours is plugged directly into safe public transport lines. If the path is predictable, visible, and occupied, the city will quietly tell adults, especially women, that their education is expected, not exceptional.

Lighting as an equity tool

Field observations underline how strongly lighting patterns create or crush opportunity. Two night schools barely a kilometre apart can have opposite trends in attendance purely because one sits on a bright corner near shops and another retreats behind a dim, unmarked lane. In this regard, lighting is not just a technical service; it is an instrument of educational equity.

A future-facing plan would make “learning hours” a criterion for where and how intensely to light streets, intersections, and building edges. Around campuses that run evening classes, streetlighting can be denser, timed to stay bright through class end-times, and paired with reflective signage that clearly marks the way in. Inside the campus, generous but not harsh lighting in courtyards, stairwells, and approach paths reduces fear without turning the place into a fortress. The message this sends is subtle but powerful: the city expects people to move with purpose at night, not just dash home and bolt the door.

Designing campuses as safe urban pockets

When we sat through evening classes, the campuses that felt most welcoming had a few things in common: a visible entrance from the main road, multiple eyes on the pathway, and at least one active space like a library or canteen spilling light and sound into the courtyard. The most intimidating ones were hidden behind blank compound walls, with a single dark gate and no sign of life outside the classroom door.

School and college locations in urban areas can be designed as safe enclaves within the urban fabric.

This would mean:Orienting main entrances to streets with natural footfall rather than back alleys. Use of transparent or semi-transparent boundary treatments around gates so that activity is visible both ways.Clustering active functions – canteen, community room, admin office – along main internal paths so that learners are never walking past long dead edges after class.

Multipurpose courtyards and small plazas just inside the gate can double as community spaces in the evening-places where families wait, informal vendors set up carts, and peer groups meet before and after class. The more legitimate activity surrounds a night school, the less it feels like an island that is isolated in the middle of a hostile city.

Mobility and women’s right to learn at night

In every city visited, the silhouette of the typical night school learner had a gendered shape: women arriving in small groups, waiting for each other at corners, calculating the last bus home. Their ability to use the night was directly tied to mobility options they considered safe, well-lit walking routes, busy bus stops, shared autos they could fill with familiar faces.

Urban transportation planning can directly expand or shrink women’s educational horizons. Giving priority to frequent and reliable evening services along routes that link working-class neighborhoods with educational clusters is one step in the right direction. Adding another layer of safety are “last-mile” solutions in the form of clearly marked, monitored auto stands or community e-rickshaw routes around major night school zones. Even simple design choices matter at stops: seating where women are not forced into dark corners, clear sightlines onto the road, and nearby mixed-use activity rather than isolated empty lots.

Planners and education departments can work together to map where the demand for night learning among women is high and overlay that with current and proposed transport lines. The resulting map is not only a transport blueprint but a gendered education plan.

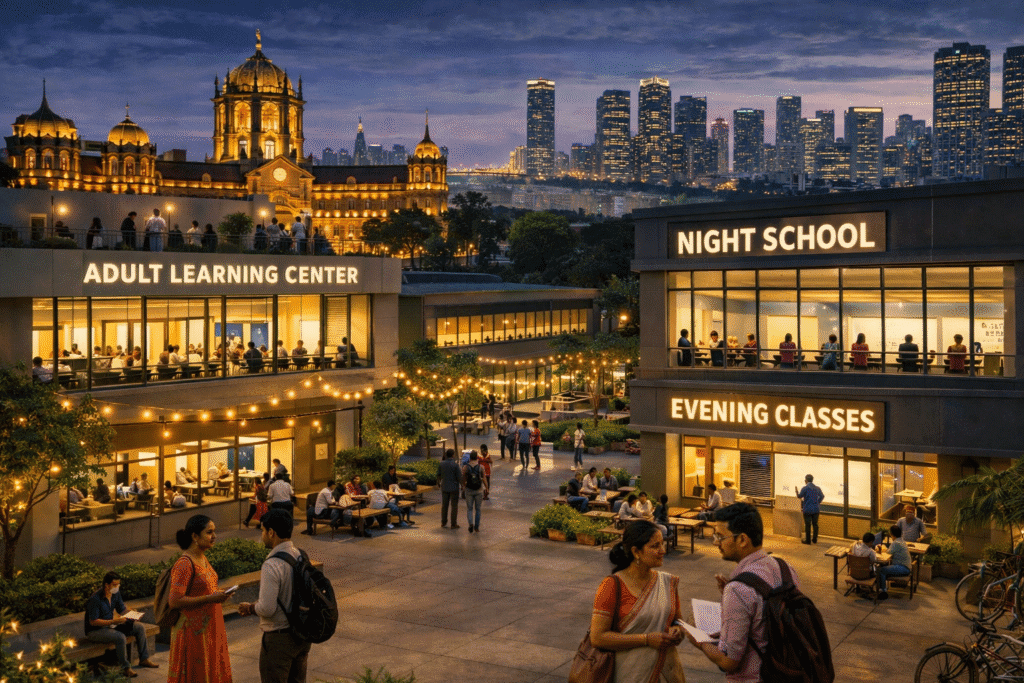

From schools to 24×7 learning districts

Most Indian cities already have clusters where multiple institutions sit close: schools, ITIs, coaching centres, colleges, training institutes. Field observations suggest that when these are planned together as “learning districts” rather than standalone compounds, they can support night education far better.

Imagine a district where, A shared, light-filled pedestrian spine connects multiple campuses.

The ground floors along this spine are reserved or incentivised for learner-friendly uses, affordable eateries, stationery and bookshops, counselling kiosks, small libraries, co-study spaces.

Public transport nodes are integrated at both ends, making it natural for the working city to flow in and out even after office hours.

Such districts can host staggered timings, school children in the day, adult learners in the evening, community events, and libraries open into the night. For urban planners, this is efficient land and infrastructure use; for learners, it is a visible statement that the city makes room for education at every hour of life. Accessibility beyond ramps and lifts. Accessibility in night school campuses is often reduced to a checklist of ramps, lifts, and railings. Adult learners, however, carry a wider array of constraints: late work shifts, caregiving responsibilities, age-related fatigue, and in some cases, disabilities obtained through labour.

A truly accessible after-hours campus would therefore consider : Shorter walking distances from public transportation drop-off points to classrooms. Compact layouts, or vertical campuses with reliable lifts and resting points.

Clear, high-contrast signage is visible at night, so first-time learners don’t have to wander through dark, confusing corridors. Seating and waiting areas for older learners or those with health problems that may need to rest before class.

If planners and architects co-design with adult learners, asking them to walk their actual route from bus stop to bench and noting every discomfort point, the campus plan will change: more benches, fewer blind corners, closer toilets, and better wayfinding. These are small moves with big consequences for who feels the campus is “for them.” Policy, data, and the politics of visibility One of the reasons that night schools remain neglected is because they are all but invisible in standard urban datasets. Attendance spikes and drops linked to changes in transport, failures in lighting, or new construction rarely make their way into official planning documents, even though these shifts are registered at once by teachers and students. Simple feedback loops can be built by urban planners and municipal bodies: joint audits of night school catchment areas; regular safety walks with learners, especially women; data dashboards tracking evening footfall along learning routes. A broken streetlight or disrupted bus route framed as an education issue-not just a civic inconvenience changes the urgency of fixing it. What our field visits drove home is the fact that night schools are not marginal add-ons to the daytime city, they are stress-tests of how inclusive the urban design really is. A city that works only for people moving between office, mall, and gated home between 9 and 9 is a city that quietly excludes millions who work odd hours and study even later. If planners start to view every evening learner as a design client, the priorities change: from car speeds to walking safety, from empty “clean” streets to lively, mixed-use corridors, from fortress schools to porous, welcoming campuses. When the city is sleeping and they are studying, the question is not whether these learners are determined enough. It is whether the urban landscape chooses to walk with them or quietly push them back home.

Chatura Juwatkar and Prajakta Kadam are media educators who believe in amplifying stories of resilience, learning, and unsung changemakers through their work.