Aishwarya Rajput | 7th December 2025

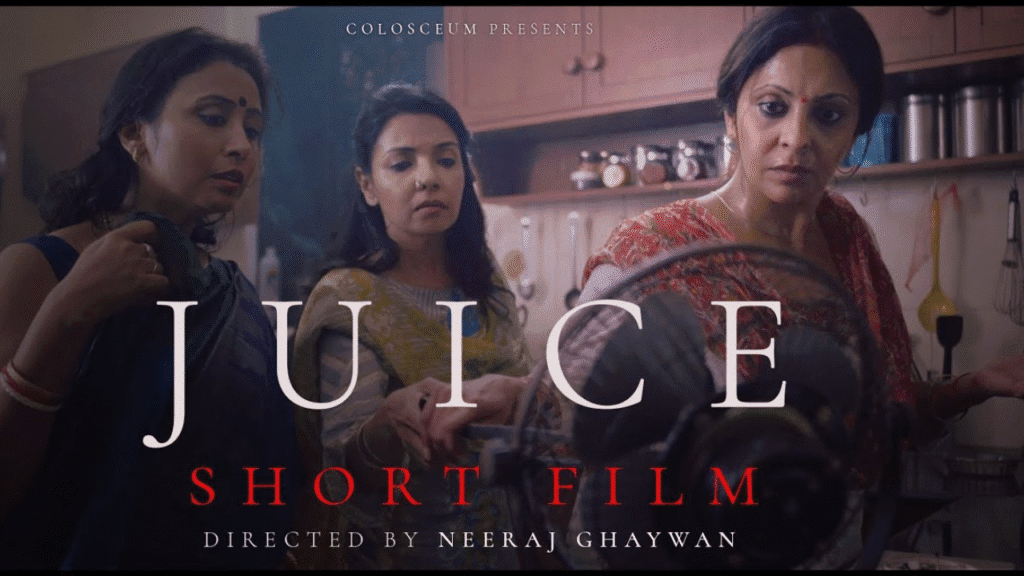

No dramatic confrontation, no guilt, no shame, no shouting, just holding up the mirror to expose the “misogyny hidden in the bone marrow of our male-dominated society.” The 2017 short film Juice, directed by Neeraj Ghaywan, is a powerful text that offers a space to reflect on everyday inequalities. It is a critique of patriarchy embedded within the routines of middle-class Indian households. Through the lens of a simple family get-together, Juice reveals how gender roles, privilege, and entitlement are subtly and persistently reproduced.

Synopsis & Cinematic Setup

On a summer evening, a middle-class couple, Mr and Mrs Singh (Manish Chaudhari and Shefali Shah), host a small get-together for friends and family. The men gather in the living room: relaxed, sipping drinks, chatting about politics, work, and even mocking powerful women (“a female boss can’t handle the pressure,” one complains).

Meanwhile, the women, including Mrs Singh, and the domestic help are confined to the kitchen, where they chop vegetables, knead dough, cook snacks, and serve the men. Sweat, heat, physical labour, and invisibility mark their evening.

As the party proceeds, the film compares the male banter with the muffled sounds of sizzling food, the crackle of dough, and the occasional grunt of fatigue from the kitchen, creating a visceral sense of inequality through atmosphere. Gradually, the viewer senses the growing discomfort of Mrs Singh. Finally, in a moment both simple and radical, she pours a glass of chilled orange juice, drags a chair into the living room near the air cooler, and sits there. The laughter dies. The men, including her husband, stare at her. Silence fills the space. Her silent gaze speaks louder than words ever could.

Key Themes & Message

By choosing a familiar, everyday setting, the film shows how patriarchy doesn’t always manifest as violence or overt oppression; sometimes it operates through the mundane routines that we rarely question. Women are in a cramped kitchen space, in heat and working while men are chilling outside in front of the cooler, passing the orders, waiting for food and commenting on working women. The pregnant woman was said to resign from her job, and the woman who had a love marriage was told to have a child. All these aspects show how, even in modern times, women are treated like people who need to be ordered around. This division is not accidental; it reflects culturally entrenched norms about who belongs where, who deserves rest and leisure, and who’s destined to labour.

The men’s conversation, casual jokes about female bosses, dismissive remarks about working women, and subtle insistence on traditional gender roles reveal how misogyny is normalised, even in ’modern’ households.

Meanwhile, the women in the kitchen and even the domestic help silently accept this. They clean, cook, serve, and disappear into the background. Their labour is invisible; their fatigue unacknowledged. The film even shows how children are socialised into these roles. A little girl is asked to serve food to her brothers, a scene that speaks volumes about intergenerational transmission of patriarchal norms.

The climax of the film, the glass of juice, the chair, the cooler, the living room, is not a loud rebellion; it is a silent assertion of dignity. Mrs Singh doesn’t reprimand anyone. She just claims her space. In that quiet act, the film transforms domestic routine into resistance, privilege into equity, invisibility into visibility.

This subtle but courageous act is what makes Juice a compelling work. It doesn’t preach; it reveals. It doesn’t dramatise; it mirrors. And in doing so, it calls on the audience to recognise, perhaps for the first time, injustices that might exist even under their own roof.

The Strength of the Short Film Format

In Juice, the 15-minute runtime is enough to deliver a full narrative arc, character development, social critique, and emotional catharsis. The minimalism, in dialogue, in plot, in spectacle, is intentional. The film doesn’t rely on dramatic confrontations or sensationalism. Instead, it uses everyday realism, mundane domestic chores, normal conversations, and familiar surroundings. This realism makes the message more relatable, more universal. As one review states: “We have all seen ‘Juice’ before in our real life.”

A large part of the film’s power comes from the performance of Shefali Shah as Mrs Singh. Critics have noted that she “emotes primarily through her expressions”, her reluctant patience, simmering frustration, and final assertion are conveyed not through words but silences, glances, and posture.

Moreover, the director’s use of sound and contrast, between the cool living room and suffocating kitchen, between chatter and silence, between privilege and labour, amplifies the theme without overt exposition.

The film doesn’t tell us what to do; it shows us what is. This reflective approach encourages self-awareness, not guilt or shame, but recognition. By holding up a mirror to familiar spaces, the film creates an opportunity for introspection. It invites viewers, especially those from households where such divisions are taken for granted, to question, to discuss, to reconsider.

Limitations & Critical Reflection

The film ends with Mrs Singh’s act of defiance. But it doesn’t show the aftermath. Does this small assertion lead to lasting change in her household? Do the husband or male guests re-evaluate their attitudes? Do the next generation, the children, change? The film leaves these questions unanswered.

Some critics argue that by showing mostly women quietly bearing the burden, the film risks reinforcing the very stereotype it critiques: that women’s role is to manage the home, without real voice, until the rare moment they “assert” themselves. Additionally, some have pointed out that the film’s portrayal of men is rather uniformly negative, which might come across as misandrist to some viewers.

While Juice is freely available on YouTube, its impact depends on who watches it and whether they choose to reflect, discuss, and act. In many households where norms are deeply entrenched, a 15-minute film may provoke discomfort for a moment, but whether that discomfort translates into change is uncertain.

Relevance for Reflection

Juice offers us the idea that not all messages need to be loud or confrontational. Sometimes, showing a mirror can be more powerful than sermons. It stands as a testament to the potential of subtle, realist storytelling.

In resource-constrained contexts, such as short films allow creators to explore sensitive social issues with minimal budget and time, yet maximum impact. Their brevity demands discipline and clarity, which often leads to compelling narratives.

Films like Juice show how gender inequality is sustained through accepted social norms, internalised attitudes, spatial arrangements, and silence. Addressing these requires nuanced strategies, awareness-building, introspection, and conversations.

A film can spark reflection, but transformation in minds, attitudes, and behaviour often requires more discussion, education, and follow-up actions. Juice promotes questions like: What are the invisible structures of power within households? How does spatial arrangement in homes reflect broader social hierarchies? Can small acts of assertion lead to systemic change?

In the crowded landscape of social-issue films, Juice stands out, not for loud denunciations or dramatic showdowns, but for quiet resilience. In its 15 minutes, it exposes how patriarchy lives not only in public institutions or workplaces, but within the walls of our homes, in the most mundane routines. It reminds us that sometimes, perhaps most powerfully, resistance can be as simple and profound as a woman claiming her seat, a glass of juice in her hand, a chair pulled under her.

Aishwarya Rajput is a media researcher and writer exploring the intersections of cinema, culture, and community narratives through an academic and creative lens.